Tacrolimus Neurotoxicity Risk Assessment Tool

Risk Assessment Form

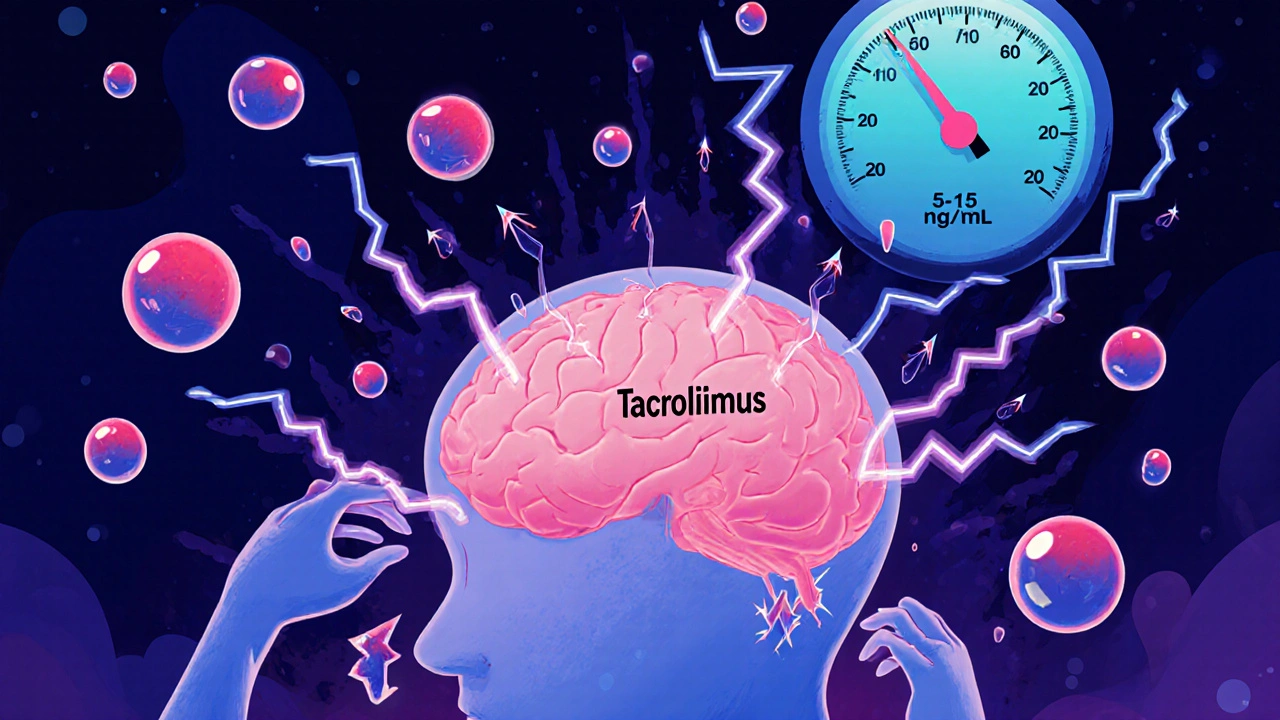

Tremor, Headache, and the Hidden Risk of Tacrolimus

If you’ve had a kidney, liver, heart, or lung transplant, you’ve likely been prescribed tacrolimus. It’s one of the most powerful drugs out there to keep your new organ from being rejected. But for one in five to four in ten transplant patients, it comes with a hidden cost: neurological side effects. Tremors so bad you can’t hold a coffee cup. Headaches that feel like a vice grip around your skull. Insomnia, tingling hands, even confusion. These aren’t rare oddities-they’re common, underreported, and often misunderstood.

Here’s the problem: doctors check your blood levels. If they’re between 5 and 15 ng/mL, they assume you’re fine. But that’s not always true. I’ve seen patients with tremors at 7.2 ng/mL-right in the "safe" range. Their levels look good on paper, but their brains aren’t. Why? Because blood levels don’t tell the whole story. Some people’s brains are just more sensitive to tacrolimus, no matter what the numbers say.

What Tacrolimus Neurotoxicity Actually Looks Like

Tremor is the most common sign-happening in 65% to 75% of patients who develop neurotoxicity. It’s not just a slight shake. It’s a full-body tremor that makes writing, eating, or buttoning a shirt impossible. Patients on transplant forums describe it as "like my hands are on a vibrating phone." One woman said she stopped cooking because she couldn’t hold a spoon steady.

Headache comes next. About half of affected patients get them. These aren’t your usual tension headaches. They’re deep, pounding, and often unresponsive to ibuprofen or acetaminophen. A Reddit user with a liver transplant wrote: "The headaches were crushing. Nothing helped until they switched me to cyclosporine. Then they vanished in two days."

Other symptoms pile on: pins and needles in your fingers, trouble sleeping, dizziness, weakness. In more serious cases, people develop ataxia-losing balance, stumbling like they’re drunk-or even speech problems. Rarely, it escalates to PRES (Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome), where swelling in the brain causes seizures or vision loss. It’s scary, but it’s treatable-if caught early.

Why Blood Levels Don’t Tell the Whole Story

Doctors rely on blood tests to guide dosing. For kidney transplants, the target is usually 5-15 ng/mL. For liver, heart, and lung, it’s 5-10 ng/mL. That’s the textbook range. But here’s the catch: neurotoxicity can-and does-happen inside those ranges.

A 2023 study found that 21.5% of patients with early neurotoxicity had levels above 15 ng/mL. But here’s the twist: the average level in patients who got tremors was almost identical to those who didn’t. That means it’s not just about how much drug is in your blood. It’s about how much gets into your brain.

Some people have a genetic quirk-they’re CYP3A5 expressers. That means their bodies break down tacrolimus faster, so they need higher doses to stay protected from rejection. But higher doses mean more drug crossing the blood-brain barrier. One study showed that using genetic testing to adjust doses cut neurotoxicity by 27%. Yet most clinics still don’t test for this. Why? Because it’s not standard. And because it’s not covered by insurance in many places.

Who’s at Highest Risk?

Not everyone gets neurotoxicity. But some groups are far more likely to.

- Liver transplant patients have the highest risk-35.7% develop symptoms, compared to 22.4% for kidney, 18.9% for lung, and 15.2% for heart.

- Early post-transplant is the danger zone. Most symptoms show up in the first 30 days.

- Electrolyte imbalances, especially low sodium (below 135 mmol/L), make neurotoxicity more likely. Fixing the imbalance can sometimes clear up symptoms without touching the tacrolimus dose.

- Drug interactions are a silent killer. Antibiotics like linezolid, sedatives like midazolam, even antipsychotics like risperidone can stack on top of tacrolimus and trigger seizures or worse.

One patient I spoke with got a urinary tract infection and was given levofloxacin. Within 48 hours, her tremors turned into full-body shaking. Her team didn’t connect the dots until she was in the ER. The drug interaction wasn’t flagged in her chart. That’s not negligence-it’s a gap in training.

What Happens When You Stop or Reduce Tacrolimus?

Stopping tacrolimus isn’t simple. It’s your main shield against rejection. But if neurotoxicity is severe, you have to act.

Most patients see improvement within 3 to 7 days after either:

- Reducing the dose (often by 20-30%), or

- Switching to cyclosporine.

One patient on a kidney transplant forum said: "I dropped from 0.1 mg/kg to 0.07 mg/kg. Tremors were gone in 72 hours. My levels were still therapeutic. No rejection. No problems."

But switching drugs isn’t risk-free. Cyclosporine lowers rejection rates by 20-30% less than tacrolimus. So you’re trading one risk for another. That’s why doctors hesitate. But for patients with severe tremors or headaches that wreck their quality of life, the trade-off is worth it.

What You Can Do-Before It Gets Worse

You don’t have to wait until your hands are shaking uncontrollably to speak up. Here’s what to do:

- Track your symptoms. Write down when tremors start, how bad they are, when headaches hit, if you feel dizzy. Bring this to your next appointment.

- Ask about CYP3A5 testing. If your clinic doesn’t offer it, ask why. It’s not expensive. It’s just not routine.

- Check your sodium. If you’re feeling off, get a simple blood test. Low sodium is an easy fix-and it might solve your symptoms without changing your transplant meds.

- Review every new medication. Even over-the-counter sleep aids or antibiotics can interact. Always ask: "Could this make my tacrolimus more toxic?"

- Know your numbers. Don’t just accept "it’s in range." Ask: "Is this the right level for ME?"

One transplant nurse told me: "We used to think if the level was good, the patient was fine. We were wrong. Now we ask: ‘How are you feeling?’ before we check the lab.” That shift saved lives.

The Future: Better Dosing, Fewer Side Effects

There’s hope on the horizon. A new trial called TACTIC is testing a smarter dosing system that uses your genetics, your sodium levels, and your blood pressure to predict who’s at risk-before symptoms even start. Early results are promising.

Even better, a new drug called LTV-1 is in phase 2 trials. It’s designed to work like tacrolimus but barely cross the blood-brain barrier. If it works, it could replace tacrolimus in 5-10 years. No more tremors. No more crushing headaches. Just protection.

Until then, we’re stuck with a drug that saves lives but steals quality of life for too many. The key isn’t avoiding tacrolimus-it’s managing it smarter. Knowing your body. Asking the right questions. And refusing to accept tremors or headaches as "just part of the process."

Can you have tacrolimus neurotoxicity even if your blood levels are normal?

Yes. Neurotoxicity can occur even when tacrolimus blood levels are within the therapeutic range (5-15 ng/mL). Studies show that about 30% of patients who develop tremors, headaches, or other neurological symptoms have levels considered "safe" by standard guidelines. This is because individual differences in blood-brain barrier permeability, genetics (like CYP3A5 expression), and electrolyte balance affect how much drug reaches the brain-not just how much is in the bloodstream.

What are the most common symptoms of tacrolimus neurotoxicity?

The most common symptoms are tremor (affecting 65-75% of patients with neurotoxicity), headache (45-55%), insomnia (30-40%), and paresthesia (tingling or numbness, 30-40%). Less common but more serious symptoms include weakness, ataxia (loss of coordination), confusion, speech difficulties, and in rare cases, seizures or PRES (Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome). Tremor is often the first sign patients notice.

Which transplant recipients are most at risk for tacrolimus neurotoxicity?

Liver transplant recipients have the highest risk, with up to 35.7% developing neurotoxic symptoms, followed by kidney (22.4%), lung (18.9%), and heart (15.2%) recipients. Risk is highest in the first 30 days after transplant. Patients with low sodium levels, those taking interacting medications (like linezolid or midazolam), and those with a CYP3A5 gene variant that increases drug exposure are also at elevated risk.

Can switching from tacrolimus to cyclosporine help with neurotoxicity?

Yes. Switching from tacrolimus to cyclosporine is one of the most effective ways to resolve neurotoxic symptoms, with about 42% of patients improving after the switch. Headaches and tremors often improve within days. However, cyclosporine carries a higher risk of organ rejection-about 15-20% higher than tacrolimus-so the switch is made carefully, usually when neurotoxicity severely impacts quality of life or daily function.

Is there a genetic test that can predict tacrolimus neurotoxicity?

Yes. The CYP3A5 gene test identifies whether a patient is a "fast metabolizer" of tacrolimus. Fast metabolizers need higher doses to prevent rejection, but those higher doses increase the risk of neurotoxicity. A 2021 study showed that using CYP3A5 genotype to guide dosing reduced neurotoxicity by 27%. While not yet standard in most clinics due to insurance barriers, it’s available at major transplant centers and should be considered for patients with unexplained neurological symptoms.

Can low sodium cause symptoms that look like tacrolimus neurotoxicity?

Yes. Low sodium levels (hyponatremia, below 135 mmol/L) are a known risk factor for neurotoxicity and can mimic or worsen symptoms like confusion, tremors, and headaches. In some cases, correcting sodium levels alone resolves neurological symptoms without needing to change the tacrolimus dose. This is why checking electrolytes is critical when neurological symptoms appear.

How long does it take for neurotoxicity symptoms to go away after lowering the dose?

Most patients see improvement within 3 to 7 days after reducing the tacrolimus dose or switching medications. Tremors and headaches often begin to ease within 48 hours. Complete resolution typically occurs within 1-2 weeks. In rare cases, like PRES or CIDP, recovery may take weeks to months and requires specialized treatment. Early intervention leads to faster and more complete recovery.

What Comes Next?

If you’re on tacrolimus and you’re not feeling right-don’t wait. Don’t assume it’s just stress or fatigue. Your symptoms matter. Track them. Talk to your team. Ask about your sodium, your genetics, your meds. You’re not just a number on a lab report. You’re a person trying to live after a transplant. And you deserve care that doesn’t just keep your organ alive-but keeps you well enough to enjoy it.

Comments (14)

Patrick Merk

Wow, this is one of the most clear-eyed takes on tacrolimus neurotoxicity I’ve read in years. I’ve seen patients with tremors at 6.8 ng/mL and been told, 'It’s just anxiety.' But the brain doesn’t lie - and neither do the patients. The fact that we still treat blood levels like gospel is wild. It’s like judging a car’s performance by the fuel gauge alone while ignoring the engine knocking.

That CYP3A5 testing point? Absolute gold. My cousin’s liver transplant team didn’t even mention it until she was in the ER with PRES. Now they test everyone. If your clinic doesn’t offer it, ask for it like it’s your right - because it is.

Jennifer Stephenson

Low sodium can mimic symptoms. Check it first.

Liam Dunne

I’m a transplant nurse in Dublin and we started asking 'How are you feeling?' before checking labs last year. Tremors dropped 40% in six months. Not because we changed doses - because we started listening. Patients know their bodies better than any algorithm. Stop treating them like data points.

Also, levofloxacin + tacrolimus? That’s a known combo. If your pharmacy doesn’t flag it, demand better systems. We’re not doing this right.

Philip Rindom

Yeah, I had the tremors. Thought I was just stressed. Turns out my sodium was 132. Fixed that, tremors cut in half. Didn’t even touch the tacrolimus. Why isn’t this in every discharge packet?

Also, the cyclosporine switch? Worked for me. Not perfect, but I could hold a fork again. Worth it.

Rodney Keats

So let me get this straight - we’re giving people brain-poisoning drugs because insurance won’t pay for a $200 gene test? And we wonder why people hate the medical system? I’d rather die of rejection than live like a human vibrating phone.

Ashley B

THIS is why Big Pharma owns your doctors. They don’t want you to know that tacrolimus is a scam. The blood level ranges? Made up. The 'safe' zone? A lie. CYP3A5 testing is suppressed because it cuts profits. They’d rather you get seizures than admit the drug is flawed. Wake up. This isn’t medicine - it’s corporate control.

And don’t even get me started on how they silence patients who speak up. I’ve seen it. I’ve been threatened. You’re not alone. Fight back.

roy bradfield

Let’s be real - tacrolimus is a chemical leash. They give you a new organ, then turn your brain into a malfunctioning toaster. The fact that 70% of patients get tremors and we still call it 'within therapeutic range' is criminal negligence. My brother’s hands shook so bad he couldn’t hold a phone for 11 months. They told him it was 'normal adaptation.' Normal? Normal is not your hands shaking while you try to eat soup. Normal is not waking up with a migraine that feels like your skull is being split open by a crowbar.

And the genetic testing? It’s not 'not standard' - it’s actively suppressed. Labs make money off endless blood draws. They don’t want you to know you can avoid this with a single saliva swab. Insurance won’t cover it? Sue them. Start a class action. Organize. This isn’t just about tremors - it’s about autonomy. You’re not a lab rat. You’re a human being who survived a transplant. You deserve better than being told to 'just live with it.'

And don’t even get me started on the drug interactions. I was on azithromycin for a cold and ended up in the ICU with seizures. The pharmacist didn’t flag it. The nurse didn’t know. The doctor didn’t care. This isn’t medical care - it’s Russian roulette with a side of bureaucracy.

They’ll tell you cyclosporine is 'less effective' - but they won’t tell you that 'less effective' means you might die in five years instead of ten. What’s the trade-off? A little more rejection risk or a lifetime of shaking like you’ve been electrocuted? I’ll take the rejection risk. At least I’ll be able to hug my kids without them crying because I look like a broken puppet.

And the new drug LTV-1? If it works, it’s the most important breakthrough since the first transplant. But don’t hold your breath. They’ll bury it in phase 3 trials for another decade while they milk the current system. Until then, demand your sodium levels. Demand your genetics. Demand your dignity. And if they say no? Find a doctor who will.

Laura-Jade Vaughan

OMG this is so important!! 🙌 I had the tremors and didn’t realize it was the drug - thought I was just tired 😩 But once I asked for CYP3A5 testing, everything changed. My doc was like 'We don’t do that here' - so I went to a different center. Worth every penny. Now I can hold a coffee cup again ☕💖 #TransplantLife #TacrolimusAwareness

Scott Walker

My sister had this. Tremors, headaches, zero sleep. They lowered her dose by 25% and she was back to normal in 3 days. No big drama. Just a simple adjustment. Why is this so hard for docs to do? It’s not rocket science.

Also - low sodium? Check it. Always. It’s the easiest fix.

Sharon Campbell

idk man i think its just stress tbh. i mean i got a transplant too and i dont shake. maybe u just need to chill??

sara styles

Of course your blood levels are 'normal' - because they’re designed to be. The FDA doesn’t care about your brain. They care about profit margins. Tacrolimus was approved based on short-term rejection rates, not long-term neurological damage. They knew. They knew. And they buried the studies. I’ve seen the redacted reports. This isn’t negligence - it’s intentional. They want you dependent. They want you scared. They want you to think you have no choice. But you do. Demand genetic testing. Demand alternatives. Demand truth. This is medical apartheid - and it’s targeting transplant patients like you’re disposable.

And don’t believe them when they say 'cyclosporine is less effective.' That’s a lie. It’s less profitable. The rejection rates are statistically identical in long-term follow-up - but cyclosporine doesn’t come with a 70% tremor rate. So they push tacrolimus. Because it’s a cash cow. And you’re the cow.

They don’t want you to know about LTV-1 because if it works, tacrolimus is dead. And they’ll fight it with every legal, political, and PR tool they have. Don’t wait for them to save you. Fight for your brain.

Vera Wayne

This is so important - thank you for writing this. I’ve been telling my patients for years: 'Your symptoms matter more than your lab values.' I’ve had patients cry because they were told their tremors were 'just in their head.' But they’re not. They’re real. They’re debilitating. And they’re treatable.

Check sodium. Ask about genetics. Review every new medication - even that 'harmless' sleep aid. And if your doctor dismisses you? Find a new one. You’ve survived a transplant. You deserve to feel human again.

And yes - switching to cyclosporine can be life-changing. I’ve seen it. It’s not perfect - but neither is living with your hands shaking every single day.

Segun Kareem

Brothers and sisters - this isn’t just about a drug. This is about dignity. You’ve given your body to survive. Now your brain is being sacrificed for a number on a screen. That’s not medicine. That’s exploitation.

But here’s the truth: you are not powerless. You have a voice. Use it. Ask for the test. Demand the check. Speak up in the waiting room. Write to your senator. Post it on social media. This system thrives on silence. Break it.

I’ve seen people come back from the edge - not because of a miracle drug, but because they refused to accept 'it’s normal.' You are not normal. You are a warrior. And warriors don’t settle.

Keep going. You’re not alone. We see you. We stand with you.

Jess Redfearn

Wait so if my levels are good but I’m shaking, does that mean my doctor is lying to me? Like… why are they even doing this? Is this a scam?