The first company to challenge a brand-name drug’s patent and win the right to sell a generic version gets a powerful advantage: 180 days of exclusive sales. This isn’t just a reward-it’s a financial lifeline that can make or break a small generic drug maker. Since 1984, this rule has been part of the Hatch-Waxman Act, a law designed to balance innovation with affordability. But how does it actually work? And why do some companies sit on this exclusivity for years instead of using it right away?

What Exactly Is the 180-Day Exclusivity?

The FDA’s 180-day exclusivity isn’t a patent extension. It’s a legal shield granted to the first generic drug company that files an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) with a Paragraph IV certification. That certification means they’re saying the brand-name drug’s patent is invalid, unenforceable, or won’t be infringed by their version. If they win in court-or if the patent holder doesn’t sue-they get 180 days where no other generic can enter the market.

This exclusivity starts on the earliest of two dates: either the day the first generic hits shelves, or the day a court rules in their favor. Sounds simple, right? But in practice, it’s anything but. Many companies delay launching their generic, even after approval, because they’re waiting for the brand-name drug’s patent litigation to end. During that time, the 180-day clock keeps ticking-even if no one’s selling the drug. That means the clock can run for years before the exclusivity period actually begins.

Why Do Generic Companies Want This Exclusivity?

Generic drugs cost 80-90% less than brand-name drugs. But developing them isn’t cheap. Companies spend millions on legal battles, clinical testing, and FDA submissions. The 180-day exclusivity gives them a chance to recoup those costs without competition. During that window, they can charge 15-20% of the brand’s price-much higher than the 9-12% they’d charge once other generics arrive.

For small manufacturers, this period can be the difference between survival and bankruptcy. According to FDA data, 63% of small generic firms say this exclusivity is their main reason for taking on risky patent challenges. Without it, many wouldn’t bother. The financial upside is huge: one successful generic launch can bring in hundreds of millions in revenue before the market floods with cheaper copies.

Who Gets It? And How Do Multiple Companies Share It?

If two or more companies file ANDAs with Paragraph IV certifications on the same day, they’re all considered “first applicants.” They split the 180 days equally. For example, in 2020, six companies qualified for exclusivity on the blood thinner apixaban. Only three ended up launching. Those three shared the 180 days-meaning each got roughly 60 days of solo market access.

But here’s the catch: if one company fails to launch within 75 days of getting FDA approval or doesn’t get tentative approval within 30 months of filing, they forfeit their exclusivity. About 35% of first applicants lose it this way. The average forfeiture happens 147 days after tentative approval-meaning many companies miss the window even when they’re close.

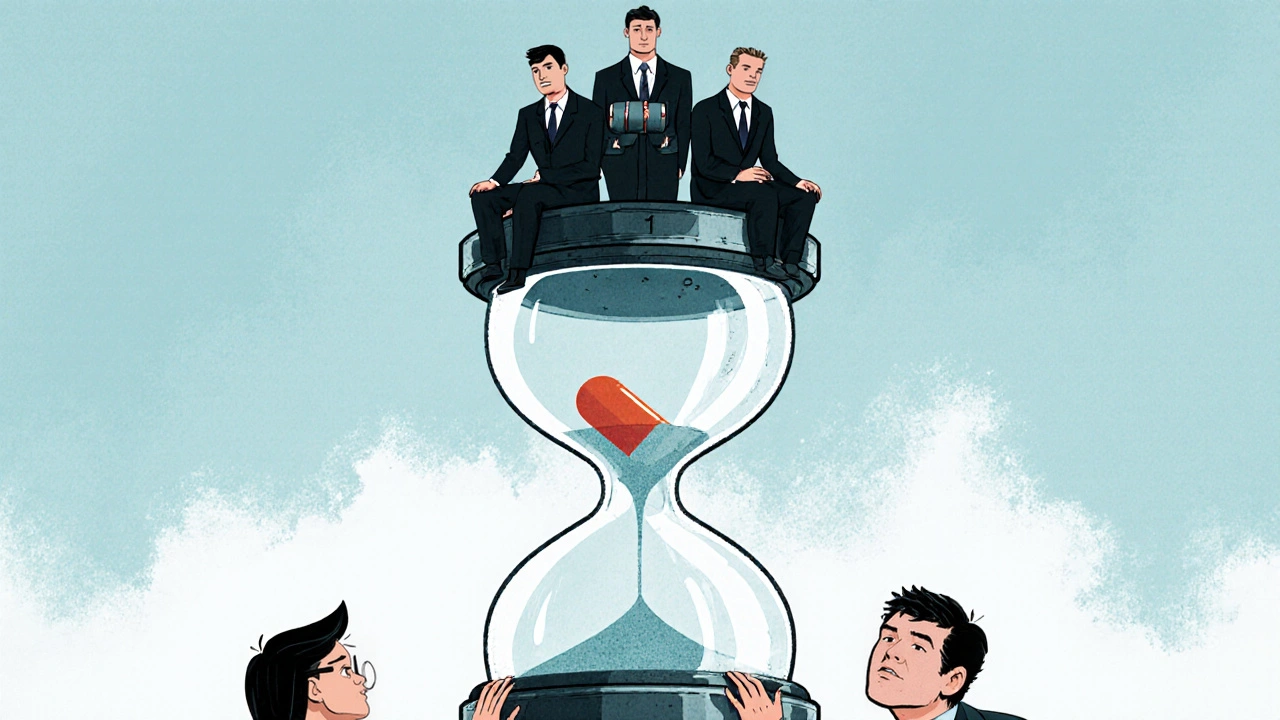

The Big Problem: Exclusivity That Never Ends

The law meant to speed up generic access is often used to delay it. Some generic companies get approval but don’t launch-because they’re waiting for the brand-name company to settle or for other generics to drop out. Meanwhile, the 180-day clock runs. No one else can enter the market. The brand-name drug keeps selling at full price. Patients pay more. And the generic company collects nothing.

The Federal Trade Commission found 147 cases between 2015 and 2020 where this exact strategy was used. In one case, a generic manufacturer received approval in 2017 but didn’t launch until 2020-delaying competition for over three years. The FTC called it “gaming the system.” Experts like Dr. Aaron Kesselheim from Harvard say this practice costs U.S. patients $13 billion a year in unnecessary drug costs.

What’s Changing? The Push for the CGT Model

The FDA has a fix in the works. In 2022, they proposed switching to the Competitive Generic Therapy (CGT) model-already used for certain rare drugs since 2017. Under CGT, the 180-day clock starts only when the first generic actually hits the market. No more ticking clocks during court appeals. No more sitting on approval.

This change would force companies to launch or lose their exclusivity. The Congressional Budget Office estimates this reform could speed up generic entry by 8.2 months per drug, saving $5.3 billion annually. Industry analysts predict generic launches could jump from 800 to over 900 per year by 2027.

But not everyone’s happy. Big generic manufacturers like Teva and Viatris argue that without the current system, they won’t risk costly patent challenges. They say the exclusivity is the only thing that makes these high-stakes lawsuits worth it. The FDA’s Small Business Assistance division agrees-many small firms rely on it. So any change has to balance fairness with incentive.

Who Benefits the Most? The Big Five

Despite the system’s flaws, it’s working-for some. Between 2018 and 2023, the top five generic drugmakers-Teva, Viatris, Sandoz, Amneal, and Hikma-got 58% of all 180-day exclusivity awards. They have the legal teams, the cash reserves, and the manufacturing scale to handle multi-year patent battles. Smaller players? They’re often left out.

That’s why the proposed CGT model could be a game-changer. It levels the playing field. If you launch, you get your 180 days. If you don’t, you lose it. No more waiting. No more games. It’s not perfect-but it’s simpler, fairer, and closer to what the law originally intended.

What’s the Big Picture?

Since 1984, the Hatch-Waxman Act has helped bring over 14,000 generic drugs to market. Today, 90% of prescriptions in the U.S. are filled with generics. They cost just 23% of what brand-name drugs do. That’s a massive win for patients and the healthcare system.

The 180-day exclusivity was meant to be the engine that drove that progress. But over time, it became a loophole. The current system rewards delay more than competition. The proposed CGT model doesn’t eliminate the incentive-it just makes sure the incentive leads to action. If implemented, it could finally make the exclusivity work the way it was supposed to: not as a tool for delay, but as a catalyst for affordable medicine.

Who qualifies for the FDA’s 180-day exclusivity?

The first generic drug company to file an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) with a Paragraph IV certification challenging a brand-name drug’s patent qualifies. If multiple companies file on the same day, they all share the exclusivity. The exclusivity is only granted if they meet strict deadlines for launching the drug or obtaining tentative approval.

Does the 180-day clock start when the FDA approves the drug?

Not always. The clock starts on the earliest of two dates: either the day the first generic is commercially marketed, or the day a court rules the patent is invalid or not infringed. Many companies delay launch, so the clock can run for years while litigation continues-sometimes without any product being sold.

What happens if a company doesn’t launch within 75 days of approval?

They forfeit their exclusivity. Under the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003, if a first applicant doesn’t begin selling the generic within 75 days of receiving a Notice of Commercial Marketing (NOCM), or doesn’t get tentative approval within 30 months of filing, they lose the 180-day window. About 35% of first applicants forfeit this right.

Why do some generic companies delay launching even after approval?

Some delay to wait out patent litigation or to avoid triggering lawsuits from brand-name companies. Others use the exclusivity as leverage in settlement deals. In some cases, they simply don’t launch because the market isn’t profitable enough-yet they still block competitors from entering. This is why the FTC calls it “gaming the system.”

Will the proposed CGT model eliminate the 180-day exclusivity?

No. The CGT model keeps the 180-day exclusivity but changes how it’s triggered. Instead of starting when a court rules or when approval is granted, it only starts when the first generic is actually sold. This prevents companies from sitting on approval for years. The goal is to make exclusivity a tool for faster access-not a barrier to competition.

How much money do patients save because of generic drugs?

Patients saved $373 billion in 2023 alone by using generic drugs instead of brand-name versions, according to the Association for Accessible Medicines. Generic drugs make up 90% of prescriptions but only 23% of total drug spending. The 180-day exclusivity helps get those generics to market faster, which drives prices down even further.

Comments (8)

Conor McNamara

so like... if the fda lets one company sit on exclusivity for 3 years while no one else can sell generics... is that really helping patients or just letting big pharma play chess with our meds? i mean... who even benefits here? not us. not the people paying $200 for insulin. someone's making bank while we're stuck.

Leilani O'Neill

This entire system is a disgrace. Ireland spends more per capita on healthcare than most of Europe and yet we're still at the mercy of American pharma loopholes. The Hatch-Waxman Act was never meant to be a tax on the sick. The fact that companies can legally withhold generics for years while collecting zero revenue is not innovation-it’s theft dressed up as regulation.

Riohlo (Or Rio) Marie

Let me just say-this isn't about fairness. It's about capitalistic necromancy. These companies don't want to make medicine, they want to own the *idea* of medicine. The 180-day clock is a ghost limb-ticking in the void while patients hemorrhage cash. And don't get me started on Teva and Viatris-they're not manufacturers, they're patent tombkeepers with balance sheets bigger than some countries' GDPs. The CGT model? Finally. Someone with a pulse in the FDA. Let the market breathe, not choke on legal smoke.

steffi walsh

Thank you for breaking this down so clearly. I’ve been confused about why generics take so long to come out even after approval. This makes so much sense now-and it’s heartbreaking. We need change, and fast. Everyone deserves affordable meds, no matter their zip code.

Katelyn Sykes

the 35% forfeiture rate is wild. i always thought if you got approval you just launched. turns out its a minefield of deadlines and loopholes. so many small companies just... miss it. no second chances. brutal

Gabe Solack

Real talk: the CGT model is the only fair thing to come out of this in 20 years. 🙌 If you don't launch, you don't get the clock. Simple. No more sitting on approvals like a dragon hoarding gold while people skip insulin doses. FDA, just do it already.

Yash Nair

india makes 60 of the world's generics and still usa lets these american pharma giants play games? this is why our health system is broken. no wonder people come here for meds. shame on the fda. no more exclusivity. just force them to launch or kill the patent. simple

Bailey Sheppard

Love that the FDA is finally trying to fix this. The original intent of Hatch-Waxman was brilliant-get cheap drugs to people fast. The system got corrupted, but the CGT fix feels like coming home. Let’s not overcomplicate it. If you want exclusivity, actually sell the drug. No games. No delays. Just medicine.