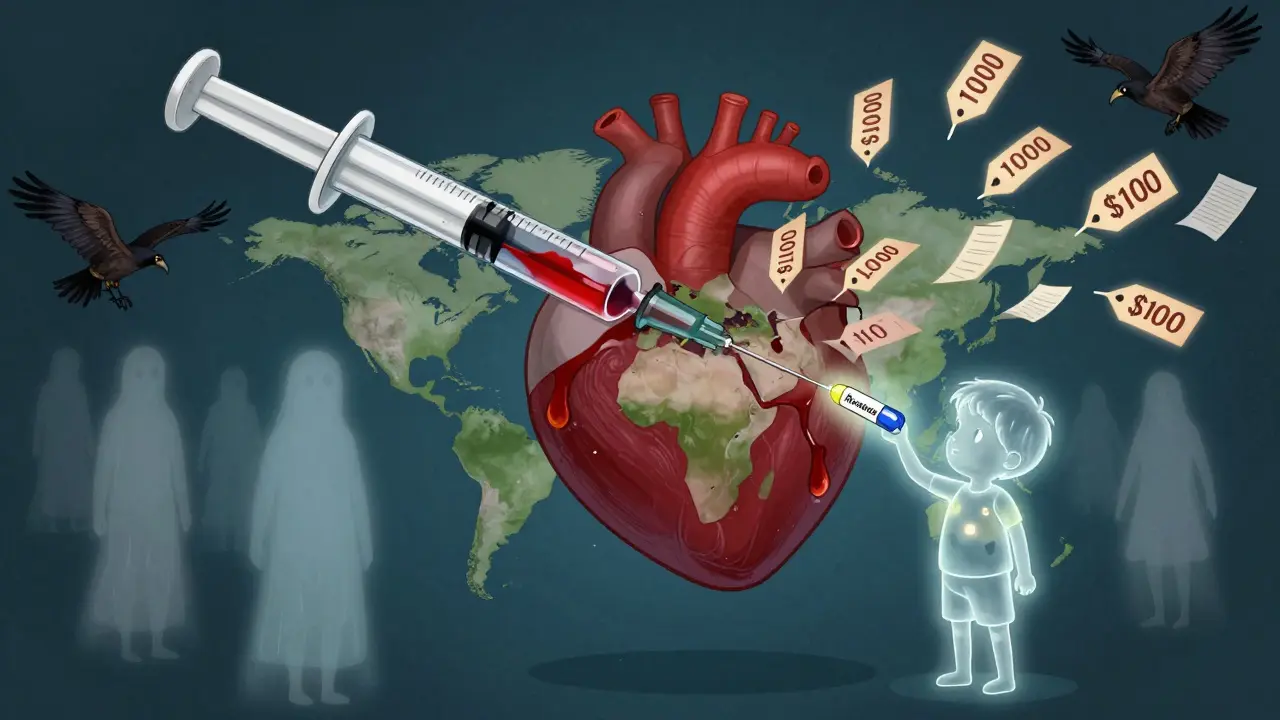

When a life-saving drug costs 100 times more in a poor country than in a rich one, it’s not a market failure-it’s a legal one. The TRIPS agreement is the reason why. Established in 1995 under the World Trade Organization (WTO), this treaty forced every member country to grant 20-year patents on pharmaceuticals. Before TRIPS, countries like India and Brazil made generic versions of HIV drugs for pennies on the dollar. After TRIPS, those factories shut down. Millions died waiting for prices to drop.

What TRIPS Actually Does

The Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, or TRIPS, wasn’t about health. It was about protecting corporate profits. It says every country must treat drug patents the same way: 20 years of exclusivity from the filing date, no exceptions. Even if a country has no drug industry, even if its people can’t afford the medicine, TRIPS still demands patent enforcement. The result? A global system where one company can hold a patent on a drug and charge $1,000 per dose while the same drug, made legally elsewhere, costs $10.

TRIPS doesn’t just cover patents. It also forces countries to restrict how generics are approved. Before TRIPS, regulators could approve a generic drug as soon as it was proven safe and effective. Now, they must wait until the patent expires-even if the patent was filed in a different country. This delay, called "data exclusivity," adds years to the monopoly. In some cases, it’s pushed beyond 20 years through "TRIPS-plus" clauses buried in trade deals with the U.S. or EU.

The Flexibility That Doesn’t Work

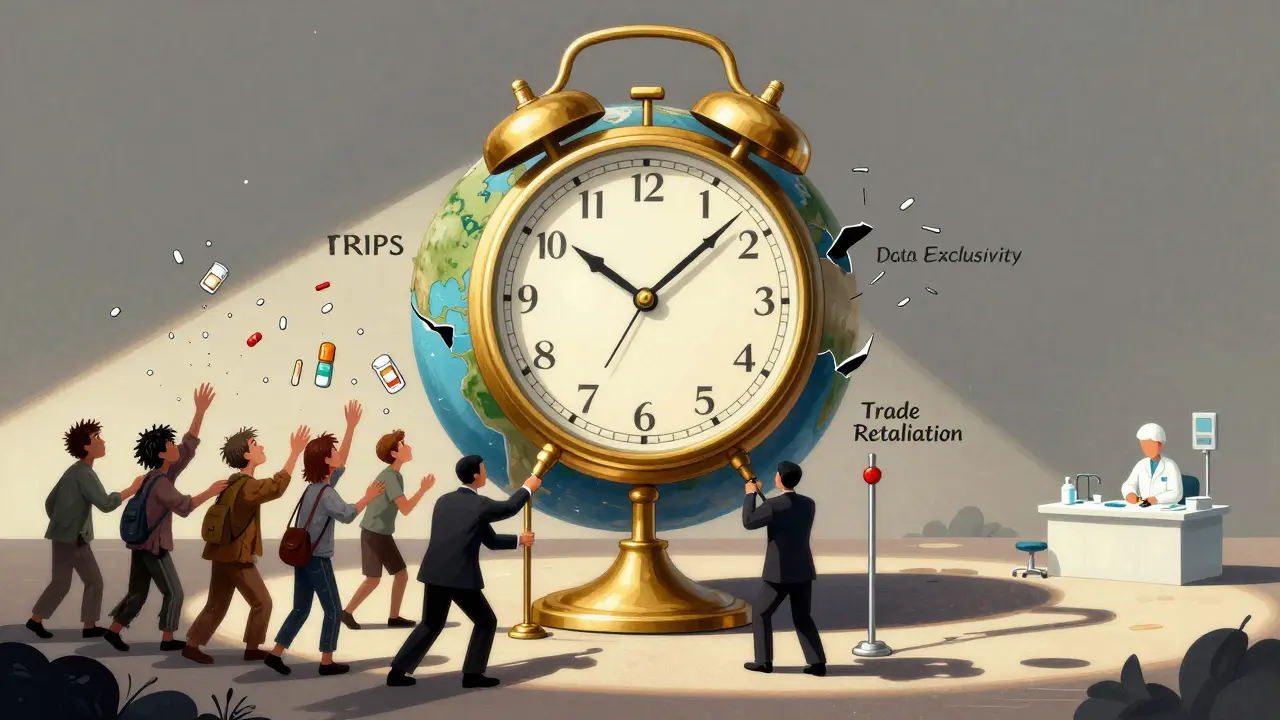

TRIPS does have "flexibilities"-legal loopholes meant to help countries in crisis. The most important one is compulsory licensing. It lets a government override a patent and allow a local company to make a generic version, usually to treat a public health emergency. Sounds simple, right? It’s not.

Article 31f of TRIPS says any compulsory license must be used "predominantly for the supply of the domestic market." That’s fine if you have a drug factory. But 48 of the world’s poorest countries have no pharmaceutical production at all. They can’t make the medicine. They can’t even legally import it from another country that made it under license-unless they jump through 78 bureaucratic hoops.

That’s where the 2005 amendment, known as Article 31bis, came in. It was supposed to fix this. It allowed countries without manufacturing capacity to import generics made under license elsewhere. Sounds like a win. Except it’s been used once. In 2008, Rwanda imported HIV drugs from Canada. It took four years. Médecins Sans Frontières helped navigate the paperwork. Apotex, the Canadian company, called the process "unworkable." And they were right.

Why No One Uses the Loopholes

Most countries don’t even try. A 2017 study of 105 low- and middle-income countries found that 83% had never issued a compulsory license. Why? Fear. Pressure. Retaliation.

Thailand tried in 2006. It issued licenses for three key drugs: HIV treatment, heart medication, and cancer therapy. Prices dropped by 30% to 80%. Then the U.S. pulled Thailand’s trade benefits. Export losses? $57 million a year. Brazil did the same with efavirenz in 2007. The U.S. Trade Representative put Brazil on its "Priority Watch List" for two years. South Africa’s 1997 law allowing generics triggered a lawsuit from 39 pharmaceutical companies. The case was dropped only after global protests.

These aren’t isolated incidents. Between 2007 and 2015, the UN recorded 423 threats of trade retaliation against countries considering compulsory licensing. The message is clear: use the law, and you’ll be punished.

The Real Solution Isn’t in the Treaty

Some say the answer is voluntary licensing-like the Medicines Patent Pool (MPP). That’s where drug companies voluntarily let generic makers produce their drugs in poor countries. It’s worked for HIV. The MPP has helped 118 countries get cheaper antiretrovirals. But here’s the catch: it covers only 44 drugs out of thousands. And 73% of those licenses are limited to sub-Saharan Africa, even though the same diseases exist in Asia and Latin America.

Compare that to the pre-TRIPS era. Between 1996 and 2001, Brazil made and exported generic HIV drugs to 127 countries. Treatment cost one-tenth of what it did under patent. Coverage hit 85%. No bureaucracy. No waiting. No threats.

Today, 2 billion people still lack regular access to essential medicines. Eighty percent of that gap is due to patent barriers. Meanwhile, the global pharmaceutical market hit $1.42 trillion in 2022. Patented drugs make up 68% of that revenue, even though they’re prescribed in only 12% of cases. The math doesn’t lie: patents aren’t about innovation-they’re about profit.

What’s Changing Now?

The pandemic forced a reckoning. In October 2020, India and South Africa proposed a TRIPS waiver for COVID-19 vaccines and treatments. After two years of lobbying, the WTO agreed-partially. The waiver covers vaccines only. No diagnostics. No treatments. And it’s temporary. By the time it took effect, most high-income countries had already hoarded doses.

But the real shift is happening outside the WTO. The UN’s 2024 High-Level Meeting on Pandemic Preparedness called for "reform of the TRIPS Agreement." The WHO’s 2023 Digital Health Strategy now mentions TRIPS flexibilities as a tool for enabling local production of digital health tech-not just pills, but diagnostic tools, sensors, and data systems.

And civil society? They’ve built tools. MSF’s Compulsory Licensing Legal Database tracks 62 attempts since 2001. Only 30% succeeded. The rest failed because of legal threats, political pressure, or lack of legal expertise. Most countries don’t have a single full-time staff member assigned to handle patent issues.

The Bottom Line

TRIPS was sold as a global standard for fairness. In reality, it’s a system designed to protect corporate monopolies at the cost of human lives. The flexibilities exist on paper. But in practice, they’re buried under legal complexity, political intimidation, and economic coercion.

The world doesn’t need more loopholes. It needs a new system. One where access to medicine isn’t a privilege granted by patent holders, but a right protected by law. Until then, people will keep dying because a treaty written in 1994 still governs how the world treats disease today.

Can any country issue a compulsory license under TRIPS?

Yes, any WTO member can issue a compulsory license for pharmaceuticals under Article 31 of TRIPS, provided it follows certain conditions: the license must be non-exclusive, limited in scope, and accompanied by adequate compensation to the patent holder. The country must also demonstrate it has tried to negotiate a voluntary license first-unless it’s facing a public health emergency. However, many countries avoid doing this due to fear of trade retaliation or legal challenges from pharmaceutical companies.

Why was the Rwanda-Canada case the only success of Article 31bis?

The Rwanda-Canada case succeeded only because of extraordinary outside support. Médecins Sans Frontières, the UN Development Programme, and Apotex worked together for four years to navigate the complex WTO notification system. The process required detailed documentation from both countries, legal reviews, and approval from the WTO’s TRIPS Council. Most low-income countries lack the legal expertise, staff, or political will to repeat this. The system was designed to be difficult-intentionally-so that few would use it.

Do TRIPS flexibilities apply to vaccines and treatments equally?

Under the original TRIPS agreement, yes-flexibilities apply to all patented medicines, including vaccines, treatments, and diagnostics. But the 2022 WTO waiver for COVID-19 vaccines only covers vaccines. It does not extend to treatments like Paxlovid or diagnostics like rapid tests. This selective approach shows how political pressure shapes what gets included. Many experts argue that excluding treatments from the waiver was a deliberate move to protect pharmaceutical profits.

How do TRIPS-plus provisions affect generic access?

TRIPS-plus provisions are extra patent rules added in bilateral trade deals-often pushed by the U.S. or EU-that go beyond what TRIPS requires. These include extending patent terms beyond 20 years, banning parallel imports, and imposing data exclusivity (blocking generic approval even after patents expire). A 2021 WTO report found 141 of 164 member states have adopted such provisions. In countries like Jordan and Morocco, these rules have delayed generic entry by 5-7 years, costing billions in avoidable healthcare spending.

Is there a legal way for countries to produce generics without violating TRIPS?

Yes, but only under strict conditions. Countries can issue compulsory licenses if they meet TRIPS requirements: they must notify the WTO, pay fair compensation, and limit production to domestic needs unless they use the Article 31bis system. Least-developed countries have until 2033 to enforce pharmaceutical patents, meaning they can legally produce or import generics without permission until then. However, even these legal paths are rarely used due to fear of political backlash, lack of technical capacity, or pressure from pharmaceutical companies.