Smoking effects: what happens to your body and your meds

Every cigarette changes your body immediately and keeps changing it over time. You don’t have to be a doctor to notice shortness of breath or a cough, but smoking also quietly changes how some medicines work and raises the chance of serious disease. This page explains the main health effects, how smoking affects common drugs, and realistic steps to quit.

Main health effects from smoking

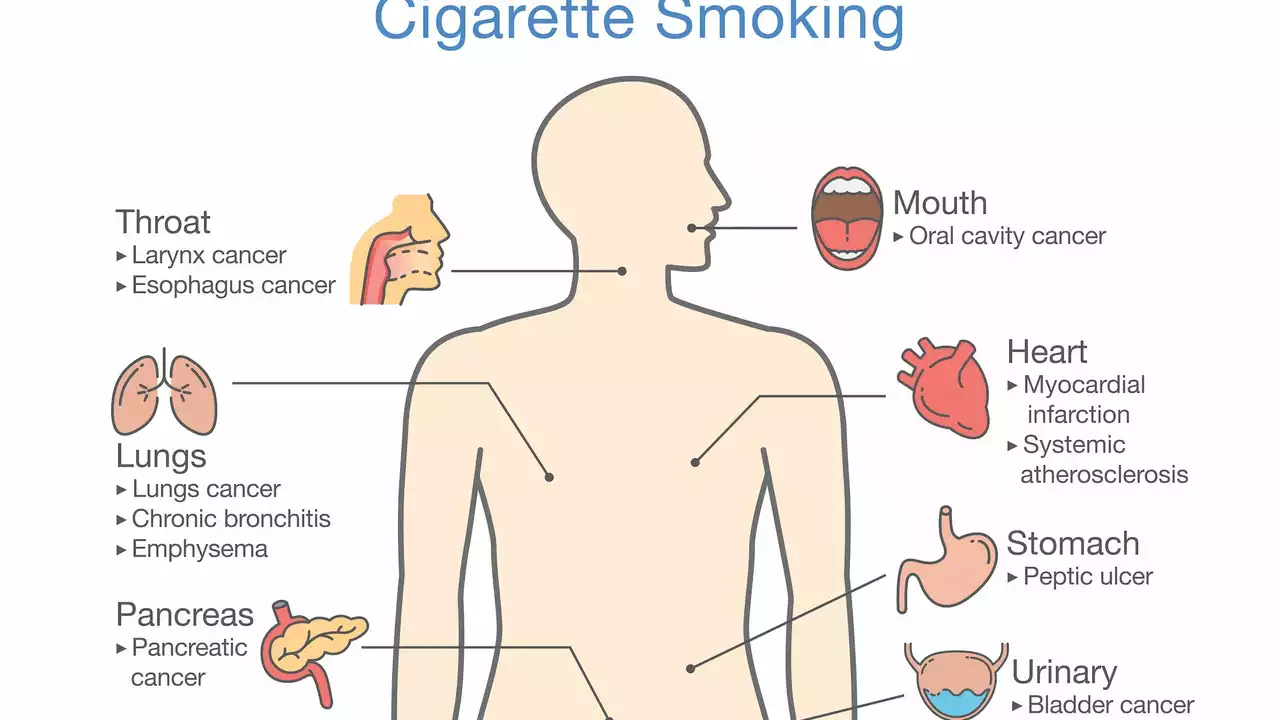

Smoking damages the lungs first. It destroys tiny air sacs, irritates airways, and makes infections and chronic bronchitis more likely. It’s the top avoidable cause of lung cancer. The heart and blood vessels suffer too: smoking raises blood pressure, speeds up clotting, and increases the odds of heart attack and stroke. Your immune response weakens, wounds heal slower, and risks for cancers in the mouth, throat, bladder, pancreas, and other organs go up. For pregnant people, smoking raises risks for miscarriage, preterm birth, and low birth weight. Even secondhand smoke causes real harm—especially to kids.

Not all damage is permanent. Good news: within hours to months after quitting your body begins to recover. Carbon monoxide levels drop within 12 hours. Heart rate and blood pressure improve within a day. In a few weeks your circulation and lung function begin to get better. After a year your risk of heart disease is much lower than if you’d kept smoking.

How smoking changes medications and what to do

Smoking alters how the liver processes some drugs. Components in cigarette smoke—especially PAHs—activate liver enzymes like CYP1A2. That makes the body clear certain meds faster. Practical examples: levels of clozapine and olanzapine (antipsychotics) and theophylline (a breathing medicine) can be lower in smokers, meaning doses that worked before quitting may become too strong or too weak after a change in smoking. If you quit, drug levels can rise quickly; doctors often reduce doses to avoid side effects.

Nicotine itself interacts with blood pressure and heart medicines and can affect insulin sensitivity. If you use nicotine replacement therapy (patches, gum) or stop smoking, tell your clinician so they can check your medications and labs. That simple step prevents bad reactions and keeps treatments effective.

Want practical quitting tips? Pick a quit date, remove tobacco and ashtrays, and plan how to handle triggers (stress, alcohol, coffee). Combine medication with support—nicotine replacement plus counseling raises your success odds. Prescription options like bupropion or varenicline help many people; both need a doctor’s advice. Use local quitlines, smartphone apps, or support groups for daily help.

If you smoke and take prescription drugs, make an appointment and bring a list of your meds. If you want to quit but worry about withdrawal or weight gain, talk about small, realistic steps. Quitting is hard, but the health gains begin fast and grow every month you stay smoke-free.