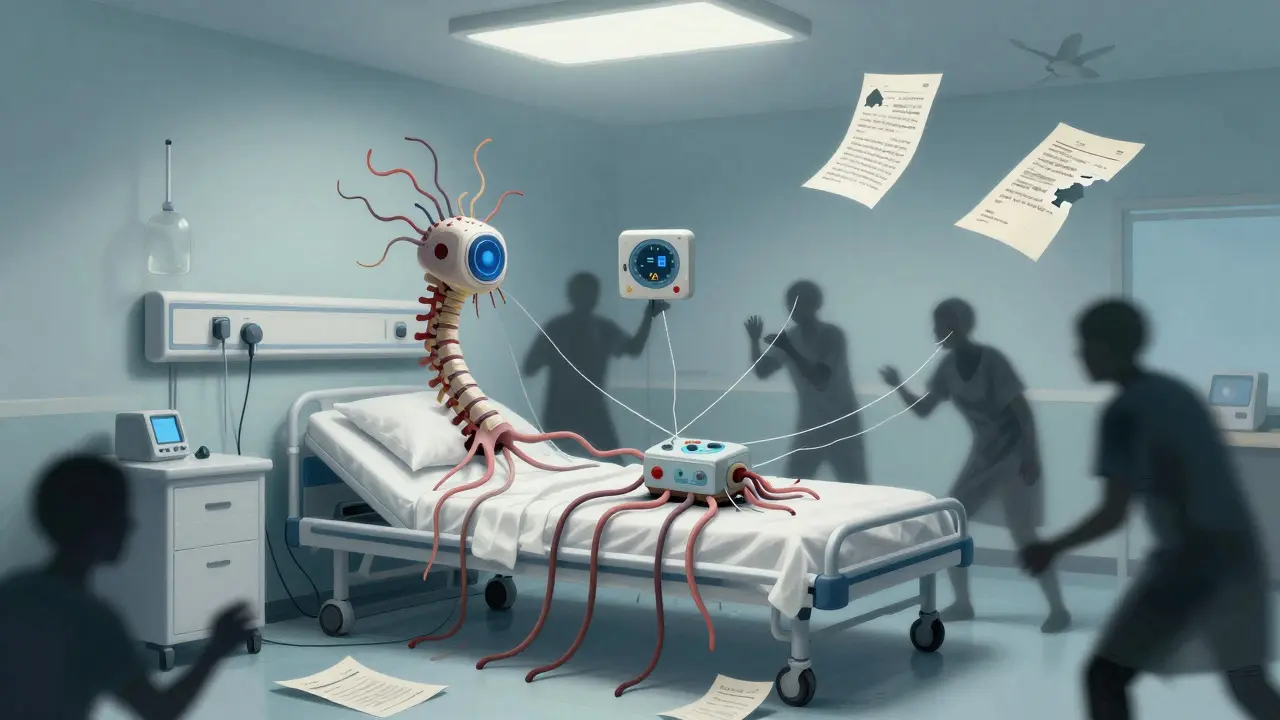

Adverse Event Reporting Assistant

Is This Reportable?

Based on FDA/EMA guidelines, most serious and unexpected reactions should be reported. This tool helps you determine if your experience should be reported to help prevent future harm.

When a new drug or medical device hits the market, it’s easy to assume it’s been thoroughly tested. Clinical trials involve hundreds or even thousands of people, right? So what could possibly go wrong? The truth is, some side effects only show up when millions of people start using a product every day. That’s where post-market surveillance comes in - the quiet, relentless system that catches dangers clinical trials missed.

Why Clinical Trials Aren’t Enough

Clinical trials are designed to prove a drug works and isn’t immediately dangerous. But they’re limited. Participants are carefully selected - no pregnant women, no elderly patients with five chronic conditions, no one taking ten other medications. And even the biggest trials rarely include more than 5,000 people. That’s not enough to spot a side effect that happens in 1 out of 10,000 patients. Take thalidomide. In the late 1950s, it was sold as a safe sleep aid and morning sickness remedy. By the time doctors realized it caused severe birth defects, over 10,000 babies were affected worldwide. That tragedy forced regulators to rethink how drugs are monitored after approval. Today, every major health agency - the FDA in the U.S., the EMA in Europe, Health Canada, TGA in Australia - requires companies to keep watching their products long after they’re sold.How Side Effects Actually Get Caught

There are two main ways side effects are spotted after approval: passive reporting and active surveillance. Passive reporting is the most common. Doctors, pharmacists, nurses, and even patients can report unexpected reactions to government systems. In the U.S., that’s MedWatch. In Europe, it’s EudraVigilance. These systems collect hundreds of thousands of reports every year. But here’s the catch: experts estimate only 6 to 10% of actual adverse events get reported. Why? Many doctors don’t have time. Patients don’t know how. And sometimes, they just assume the symptom is normal - a headache, dizziness, or rash. Active surveillance is more powerful. Instead of waiting for reports, systems actively dig through real-world data. The FDA’s Sentinel Initiative, for example, analyzes electronic health records from over 300 million Americans. It looks for patterns: Are people taking Drug X more likely to have heart rhythm problems than those taking Drug Y? Are there spikes in hospital visits after a new device is implanted? This method catches signals passive systems miss. For medical devices, it’s even trickier. A pacemaker doesn’t cause a chemical reaction - it can fail mechanically, or the wire might break after two years. That’s why the EU’s Medical Device Regulation (MDR) requires manufacturers to run Post-Market Clinical Follow-up (PMCF) studies. These aren’t optional. Companies must actively track how their devices perform in real life, collecting data from hospitals, patient registries, and even warranty claims.The Hidden Gaps in the System

You might think all this monitoring means we’re safe. But the system has serious holes. First, underreporting is massive. A 2021 Johns Hopkins study found only 12% of patients knew how to report a bad reaction. Most don’t. And even when they do, many reports are vague: “Felt weird after taking pill.” That’s not enough to prove causation. Second, delays are common. The FDA requires post-approval studies for many drugs, but a 2021 JAMA Internal Medicine study found only 29% of these studies were completed on time. The average delay? Over three years. That’s three years of people taking a drug while regulators wait for safety data. Third, small manufacturers struggle. Under the EU MDR, every device maker - even tiny startups - must now create a full Post-Market Surveillance Plan, track complaints, analyze trends, and file annual reports. A 2023 survey by Emergo by UL found 63% of device companies said they couldn’t keep up. No extra budget. No extra staff. Just more paperwork.

Real Stories Behind the Data

Behind every statistic is a person. In 2020, a cardiologist in Boston reported a rare but severe skin reaction to a new blood thinner. She filed a MedWatch report. She never heard back. She didn’t know if anyone even looked at it. She stopped reporting after that. In 2022, a patient in Australia started having seizures six months after getting a new type of spinal stimulator. Her doctor didn’t recognize the link. It took three hospital visits and a Reddit post from another patient with the same device before anyone connected the dots. That’s how we found out: not through a clinical trial, not through a regulatory audit - through a patient sharing their story online. These aren’t outliers. They’re the rule. And they’re why post-market surveillance isn’t just bureaucracy - it’s a lifeline.What’s Changing Now

The system is evolving. AI is helping. Companies like Oracle Health now use machine learning to scan social media, patient forums, and hospital records for signs of trouble. One company reported detecting safety signals 40% faster than traditional methods. Patient-reported outcomes are gaining traction. Apps now let users log symptoms daily. That data flows directly into safety databases. In the U.S., the FDA is testing ways to use wearable data - heart rate spikes, sleep patterns - to spot early warning signs. The European Union is tightening rules even further. As of 2024, all legacy devices must now prove ongoing safety through PMCF studies. No more “grandfathering in.” If you can’t show your device is still safe after five years of use, it gets pulled. And the market is responding. The global pharmacovigilance industry is worth over $5 billion and growing fast. Big players like IQVIA and Parexel now offer AI-powered signal detection tools. But the real challenge isn’t technology - it’s trust.What Patients and Doctors Can Do

You don’t need to be a regulator to help. Here’s what you can do:- If you experience something unusual after starting a new medication or device - even if it seems minor - tell your doctor. Write it down: what happened, when, and how long it lasted.

- Ask your doctor if they’ve filed a report. If they haven’t, ask why. Reporting isn’t optional for them - it’s part of their duty.

- Know where to report. In the U.S., go to fda.gov/medwatch. In Australia, use the TGA’s online portal. In Europe, contact your national health authority.

- If you’re on a new drug or device, check back with your doctor after three months. Side effects don’t always show up right away.

Comments (15)

Theo Newbold

Passive reporting is a joke. I've seen three separate cases where doctors dismissed symptoms as 'normal'-only to find out months later it was a known adverse reaction buried in a 300-page FDA safety update no one reads. The system isn't broken-it's designed to ignore the noise until it becomes a crisis.

Jay lawch

Let me tell you something they don't want you to know. The pharmaceutical industry doesn't want you to report side effects-because if enough people do, the drug gets pulled, and the stock tanks. That's why they pay doctors to downplay reactions. That's why MedWatch is buried under layers of bureaucracy. That's why your 'minor' headache is labeled 'non-serious' and tossed into a digital graveyard. They're not monitoring safety-they're managing liability. And you? You're just a data point in their profit algorithm.

Christina Weber

It's worth noting that the term 'post-market surveillance' is often misused to imply a robust, proactive system. In reality, it is a reactive, underfunded, and inconsistently enforced process that relies on voluntary reporting from overburdened clinicians and statistically insignificant patient submissions. The FDA’s Sentinel Initiative, while technically impressive, is limited by data silos, interoperability failures, and institutional inertia. Until mandatory reporting is enforced and standardized across all healthcare providers, this entire framework remains a symbolic gesture.

Cara C

I appreciate how you highlighted the patient story from Australia-those moments are what make this real. It’s easy to get lost in stats and regulations, but when someone connects with another person’s experience online and says, 'Wait, that’s what happened to me too,' that’s how change starts. Maybe the system’s flawed, but people are still finding each other. That’s hope right there.

Michael Ochieng

As someone who works in global health tech, I’ve seen how countries like Canada and Germany are ahead of the U.S. in integrating real-world data. We’re not just waiting for reports-we’re using AI to flag anomalies in pharmacy records and EHRs in near real-time. The problem isn’t the tech. It’s the willingness to share data across borders and institutions. If we treated safety like climate data-open, shared, urgent-we’d be way ahead.

Cameron Hoover

They told me the new blood thinner was 'safe.' I took it for six weeks. Then I started bleeding out of nowhere. ER. ICU. They had to reverse it with a $12,000 antidote. I filed a report. Got a form letter back. I’m not mad. I’m just… tired. If this is the best we can do, then we’re failing. And we’re failing people who don’t know how to speak up.

Stacey Smith

Stop blaming the FDA. The real problem is the medical-industrial complex. Big Pharma owns Congress. They lobby to delay post-market studies. They pay off doctors. They silence whistleblowers. This isn’t incompetence-it’s corruption. And you’re all just pawns in their game.

Ben Warren

It is both lamentable and profoundly concerning that the regulatory apparatus governing pharmaceutical and medical device safety remains fundamentally dependent upon the voluntary, inconsistent, and often ideologically compromised reporting practices of individuals who lack both the training and the incentive to accurately identify and document causal relationships between intervention and adverse outcome. The statistical power of such systems is negligible, and their epistemic reliability is, by any rigorous scientific standard, unacceptable. One cannot rely on anecdotal testimony to safeguard public health.

Teya Derksen Friesen

Canada’s system is actually better than the U.S.’s-we have mandatory reporting for certain classes of devices, and Health Canada actually follows up on high-risk signals. But even here, the burden falls on clinicians. Patients don’t know how to report. And the portals are clunky. We need a simple app. One tap. One photo of the symptom. Done. No forms. No jargon.

Sandy Crux

And yet… no one mentions that the entire premise of 'post-market surveillance' is predicated on the assumption that regulatory agencies are neutral arbiters of truth-when, in fact, they are captured institutions, beholden to corporate donors, revolving-door executives, and the myth of 'innovation at all costs.' The MDR? A performative gesture. The FDA? A rubber stamp with a fancy logo. We don't need more surveillance-we need to dismantle the architecture that made this necessary in the first place.

Hannah Taylor

my friend got a pacemaker and then started having panic attacks. she thought it was anxiety. turns out the device was emitting weird EM signals. she found out from a reddit thread. the company said 'no known issues.' lol. they’re lying. they always lie. and no one checks. just give us the pills and shut up.

Jason Silva

THEY’RE HIDING THINGS!!! 🚨 I’ve been saying this for years! The FDA and Big Pharma are in bed together! They bury the bad data, manipulate the stats, and use 'low reporting rates' as an excuse to do NOTHING! You think thalidomide was the only one? Nah. There are dozens more. And they’re still on the market. 🤫💊 #WakeUp

mukesh matav

Back home in India, we don’t even have proper reporting systems. People take generics, get sick, and just stop using the drug. No one files anything. No one cares. It’s not about bureaucracy-it’s about access. If you can’t afford the medicine, you don’t complain about side effects. You just suffer.

Peggy Adams

Why do we even bother? I reported a rash from a new antidepressant. Got an email saying 'thank you for your feedback.' That was it. Three months later, my doctor prescribed the same drug to someone else. Nothing changed. This system is a joke. I’m done.

Jerry Peterson

My sister got a hip implant in 2021. Last year, she had to get it removed because the coating started flaking off. The surgeon said, 'We’ve seen three others like this.' But the manufacturer’s website still says '99% success rate.' How? Who’s counting? If you’re not tracking every device like a serial number, you’re not monitoring-you’re guessing.